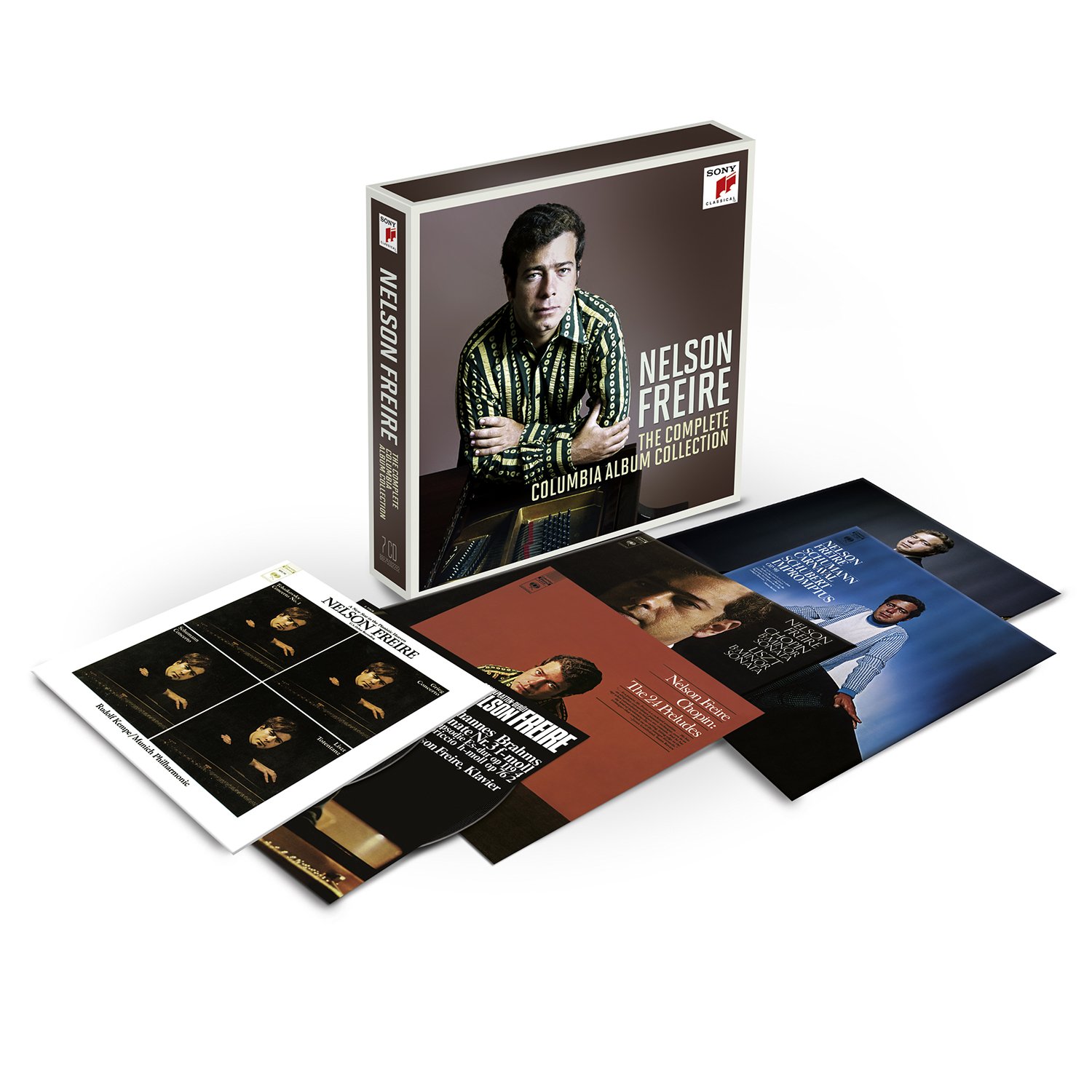

The Complete Columbia Album Collection - 7 CDs

By Presto Classic

Called “one of the most exciting new pianists of this or any other age” in Time magazine, Nelson Freire celebrates his seventieth birthday on October 18th 2014. Sony Classical marks this milestone with a special original jacket collection. It contains some of the Brazilian pianist’s earliest and most coveted recorded performances, many of which have been out of print for decades. These include four celebrated concerto collaborations with the legendary conductor Rudolf Kempe, the “Prix Edison” award winning Chopin op. 28 Préludes, and large-scale sonatas by Chopin, Liszt and Brahms. Newly remastered from the best possible sources, the discs are presented in facsimile sleeves and labels corresponding to the original LP releases. 3 LPs appear here for the first time on CD, mastered from the original analogue tapes.

An enclosed booklet offers an essay by Jed Distler, a photographic retrospective, and full discographical information. Born in Boa Esperança, Brazil, Nelson Freire played his first recital at four. At fourteen he traveled to Vienna to study with Bruno Seidlhofer, and met his longtime friend and piano duo partner Martha Argerich. He began to concertize internationally, winning the first prize at the Lisbon Vianna da Motta International Competition in 1964 and the Dinu Lipatti medal in London. The list of world class orchestras and conductors with whom Freire has worked over the past four decades is a veritable who’s who of classical music luminaries.

Tracks:

Brahms:

Piano Sonata No. 3 in F minor, Op. 5

Rhapsody in E flat major, Op. 119 No. 4

Capriccio in B minor, Op. 76 No. 2

Chopin:

Preludes (24), Op. 28

Piano Sonata No. 3 in B minor, Op. 58

Impromptu No. 4 in C sharp minor, Op. 66 'Fantaisie-Impromptu'

Mazurka No. 25 in B minor, Op. 33 No. 4

Mazurka No. 23 in D major, Op. 33 No. 2

Mazurka No. 26 in C sharp minor, Op. 41 No. 1

Polonaise No. 6 in A flat major, Op. 53 'Héroïque'

Scherzo No. 2 in B flat minor, Op. 31

Nocturne No. 5 in F sharp major, Op. 15 No. 2

Waltz No. 6 in D flat major, Op. 64 No. 1 'Minute Waltz'

Impromptu No. 2 in F sharp major, Op. 36

Étude Op. 10 No. 5 in G flat major 'Black Key'

Grieg:

Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16

Liszt:

Totentanz, S126 for piano & orchestra

Piano Sonata in B minor, S178

Schubert:

4 Impromptus, D899

Schumann:

Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 54

Carnaval, Op. 9

Tchaikovsky:

Piano Concerto No. 1 in B flat minor, Op. 23

Brahms:

Piano Sonata No. 3 in F minor, Op. 5

Rhapsody in E flat major, Op. 119 No. 4

Capriccio in B minor, Op. 76 No. 2

Chopin:

Preludes (24), Op. 28

Piano Sonata No. 3 in B minor, Op. 58

Impromptu No. 4 in C sharp minor, Op. 66 'Fantaisie-Impromptu'

Mazurka No. 25 in B minor, Op. 33 No. 4

Mazurka No. 23 in D major, Op. 33 No. 2

Mazurka No. 26 in C sharp minor, Op. 41 No. 1

Polonaise No. 6 in A flat major, Op. 53 'Héroïque'

Scherzo No. 2 in B flat minor, Op. 31

Nocturne No. 5 in F sharp major, Op. 15 No. 2

Waltz No. 6 in D flat major, Op. 64 No. 1 'Minute Waltz'

Impromptu No. 2 in F sharp major, Op. 36

Étude Op. 10 No. 5 in G flat major 'Black Key'

Grieg:

Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16

Liszt:

Totentanz, S126 for piano & orchestra

Piano Sonata in B minor, S178

Schubert:

4 Impromptus, D899

Schumann:

Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 54

Carnaval, Op. 9

Tchaikovsky:

Piano Concerto No. 1 in B flat minor, Op. 23